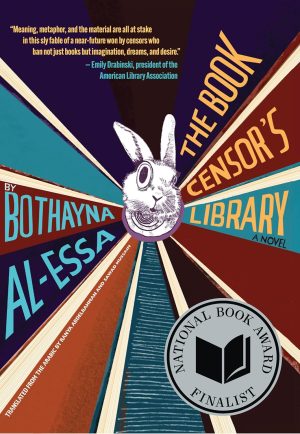

Translated by Ranya Abdelrahaman and Sawad Hussain

Book reviewers of “dystopian” novels often focus on how well iconic authors “predicted” our current world of mass surveillance, alternate realities, and grinding political crises. This helps determine whether they are classics. Orwell foresaw a forever-war of three great powers. Huxley anticipated mass-drugging of the populace. Margaret Attwood’s fear of male power hegemony crushing women’s autonomy and human rights still feels acute.

Then comes the inevitable, punctilious criticism of the iconic author for having forecast incorrectly. Orwell’s totalitarian state has been overtaken by a less comprehensive but more efficient model of regional autocrats. Huxley missed the rise of computers and the digital revolution. Attwood’s dark vision is limited by the unconscious biases of the feminism of the 1980s.

Such tea-leaf reading makes Bothayna Al-Essa’s The Book Censor’s Library (Restless Books, 261 pages) refreshing; it is couched as a fable, blessedly free of futurism. Yet it is biting, partly because of its uncanny charm, and partly because it is aimed at one contemporary autocratic regime, the Emirate of Kuwait. Al-Essa leaves little wiggle-room that the target of her satire is a living example of authoritarian power—and an example that becomes a stand-in for any authoritarian state.

Continue reading

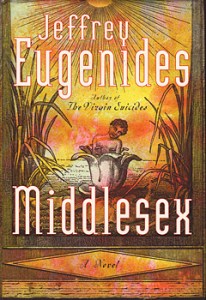

Like a hermaphrodite, Middlesex (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Jeffrey Eugenides is composed of two parts that are not usually joined together.

Like a hermaphrodite, Middlesex (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Jeffrey Eugenides is composed of two parts that are not usually joined together.