Happy New Year to all our friends. Looking back on 2019, I optimistically note that participation at Dactyl Review has increased since 2018, with many good contributions: reviews, new book announcements, and editorials. We have nine new nominations for the Dactyl Literary Award this year, and these will be in the running for the 2019 award, together with nominations from previous years when no prize was awarded.

Happy New Year to all our friends. Looking back on 2019, I optimistically note that participation at Dactyl Review has increased since 2018, with many good contributions: reviews, new book announcements, and editorials. We have nine new nominations for the Dactyl Literary Award this year, and these will be in the running for the 2019 award, together with nominations from previous years when no prize was awarded.

Although we usually announce the winner fairly early in the year, I have not yet read all the nominated books. I beg your patience. It’s a lot of very important work that I take seriously. And I also have a review of a book from my favorite literary fiction publisher, McPherson & Co., to finish and post soon. (It’s been a crazy, busy year for me.) In the meantime, I will personally match any donations (up to $500) made to Dactyl Foundation between now and the day of the award announcement. As always, and at any time in the year, your donation is fully tax-deductible. I want to take this time to mention that contributing editor U. R. Bowie reviewed Olga Tokarczuk’s, book Flights, translated into English by Jennifer Croft, which subsequently won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2019. Bowie’s review was one of the first to praise the book and his review is one of the longest and most complex to be published before the Nobel prize announcement. You read it here first. Good catch, Bowie.

I want to take this time to mention that contributing editor U. R. Bowie reviewed Olga Tokarczuk’s, book Flights, translated into English by Jennifer Croft, which subsequently won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2019. Bowie’s review was one of the first to praise the book and his review is one of the longest and most complex to be published before the Nobel prize announcement. You read it here first. Good catch, Bowie.

Looking forward to Dactyl Review‘s 10th anniversary in March of 2020, Dactyl Foundation is pursuing plans to operate as a non-profit hub for a literary publishing cooperative. Since 2010 we have been providing authors with what they need most: excellent peer reviewers, potential to receive a generous financial award, recognition for good work, and a community of like-minded authors. We hope that our cooperative venture will provide much, much more of the same and then some.

Thanks everyone for all the reading, writing and reviewing you do.

Yours truly,

V. N. Alexander, Editor, Dactyl Review

In his novel Zone 23 (SS&C Press, 483 pages) expat playwright C.J. Hopkins depicts a society, much like ours at its worse — some six or seven hundred years in the future — when any departures from prescribed ways of thinking are pathologized. Being melancholy, pondering larger philosophical questions, or contemplating the lack of fairness of the system can earn one a diagnosis of mental illness. Virtually everyone is on medication. Those who can’t be controlled by medication are deemed “Anti-Social Persons” and are removed from the society of “Normals” and relegated to various zones of abandoned and bombed-out cities, where they are eventually blown to bits by gamer-controlled drones.

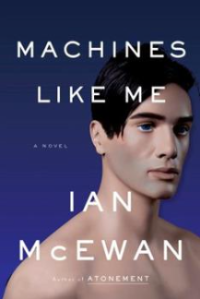

In his novel Zone 23 (SS&C Press, 483 pages) expat playwright C.J. Hopkins depicts a society, much like ours at its worse — some six or seven hundred years in the future — when any departures from prescribed ways of thinking are pathologized. Being melancholy, pondering larger philosophical questions, or contemplating the lack of fairness of the system can earn one a diagnosis of mental illness. Virtually everyone is on medication. Those who can’t be controlled by medication are deemed “Anti-Social Persons” and are removed from the society of “Normals” and relegated to various zones of abandoned and bombed-out cities, where they are eventually blown to bits by gamer-controlled drones. Machines Like Me (Nan A. Talese, 352 pages) by Ian McEwan is set in the possible world of the 1980s if Alan Turing had not died in 1954, Kennedy had not been shot in Dallas, and Britain had not won the war in the Falklands. In the story, Open Source information has allowed technological progress to sprint ahead, and the automatization of work is leading, first to high unemployment and then, presumably, to the creation of a universally idle population supported by the labor of machines. The hero, Charlie Friend, has recently purchased a life-like robot named Adam and he and his new love interest Miranda Blacke will together train and condition Adam to develop a personality and consciousness.

Machines Like Me (Nan A. Talese, 352 pages) by Ian McEwan is set in the possible world of the 1980s if Alan Turing had not died in 1954, Kennedy had not been shot in Dallas, and Britain had not won the war in the Falklands. In the story, Open Source information has allowed technological progress to sprint ahead, and the automatization of work is leading, first to high unemployment and then, presumably, to the creation of a universally idle population supported by the labor of machines. The hero, Charlie Friend, has recently purchased a life-like robot named Adam and he and his new love interest Miranda Blacke will together train and condition Adam to develop a personality and consciousness.

In his

In his

What made Orwell’s 1984 a classic? The language of this high-school required reading isn’t particularly memorable, with the obvious exception of phrases like, “war is peace,” and “ignorance is strength.” The plot swings rustily on an ill-fated romance in the first part. The lovers, Winston and Julia, are unlikable, one-dimensional, selfish anybodies. In the second part, Winston’s torturer O’Brien, like Milton’s Satan, steals the literary stage for a bit, but, even so, his evil nature lacks style, compared to, say, Medea or the Judge. Remarkably, however, I will say, that, as tragedies go, 1984 pulls its hero down lower than any Greek drama or Cormac McCarthy novel that I can think of. Winston Smith ends in total dehumanization when he accepts Big Brother into his heart as his savior.

What made Orwell’s 1984 a classic? The language of this high-school required reading isn’t particularly memorable, with the obvious exception of phrases like, “war is peace,” and “ignorance is strength.” The plot swings rustily on an ill-fated romance in the first part. The lovers, Winston and Julia, are unlikable, one-dimensional, selfish anybodies. In the second part, Winston’s torturer O’Brien, like Milton’s Satan, steals the literary stage for a bit, but, even so, his evil nature lacks style, compared to, say, Medea or the Judge. Remarkably, however, I will say, that, as tragedies go, 1984 pulls its hero down lower than any Greek drama or Cormac McCarthy novel that I can think of. Winston Smith ends in total dehumanization when he accepts Big Brother into his heart as his savior. “The Grim Reaper visits Florida wearing a silly tie. One man’s life is done…or is it? What happens if you subvert the cosmic order?”

“The Grim Reaper visits Florida wearing a silly tie. One man’s life is done…or is it? What happens if you subvert the cosmic order?” Newton’s collection of surreal stories, Seven Cries of Delight (Recital Publishing, 170 pages) was nominated by Brent Robison who, in his

Newton’s collection of surreal stories, Seven Cries of Delight (Recital Publishing, 170 pages) was nominated by Brent Robison who, in his

Happy New Year to all our friends. Looking back on 2019, I optimistically note that participation at Dactyl Review has increased since 2018, with many good contributions: reviews, new book announcements, and editorials. We have nine new nominations for the Dactyl Literary Award this year, and these will be in the running for the 2019 award, together with nominations from previous years when no prize was awarded.

Happy New Year to all our friends. Looking back on 2019, I optimistically note that participation at Dactyl Review has increased since 2018, with many good contributions: reviews, new book announcements, and editorials. We have nine new nominations for the Dactyl Literary Award this year, and these will be in the running for the 2019 award, together with nominations from previous years when no prize was awarded.