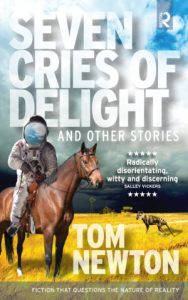

Seven Cries of Delight (Recital Publishing, 170 pages) is not like most collections of literary short stories. As legions of MFA students busily workshop their childhood drama into market-friendly “realistic” fiction, Tom Newton has clearly been following a different muse. These stories (two dozen of them!) range widely in setting and imagery and allusion, but all are hung on a solid spine: a lively curiosity about the deeper, invisible nature of what we call reality. This curiosity is expressed as speculative imaginings and unharnessed mental rovings, with an articulate, wryly humorous voice that obviously springs from a well-traveled and well-read intellect. At every turn are enjoyable discoveries of unlikely connections, unpredictable logic, and unanswerable questions.

Seven Cries of Delight (Recital Publishing, 170 pages) is not like most collections of literary short stories. As legions of MFA students busily workshop their childhood drama into market-friendly “realistic” fiction, Tom Newton has clearly been following a different muse. These stories (two dozen of them!) range widely in setting and imagery and allusion, but all are hung on a solid spine: a lively curiosity about the deeper, invisible nature of what we call reality. This curiosity is expressed as speculative imaginings and unharnessed mental rovings, with an articulate, wryly humorous voice that obviously springs from a well-traveled and well-read intellect. At every turn are enjoyable discoveries of unlikely connections, unpredictable logic, and unanswerable questions.

A few samples…. “The Best of Luck” opens the book by juxtaposing the nameless narrator’s love for idleness and an occult method for making nonsensical travel plans. “If you are a person who dislikes work and has no desire to do anything at all, you can come to The Idle House. You will be sheltered, clothed and fed, free of charge. You can stay here for as long as you want…. What is laziness? I know the definition but I am looking for something deeper: the need to describe such a quality in the first place.”

An urge to venture outside The Idle House moves this narrator to action: “I made a lipogram from my name by dropping the vowels, and converted the remaining consonants to the numerical value of the respective Hebrew letters…. As I did this, I realised that I would need a plan, if I were ever to leave. Then I had the idea that I could use the sigil to plot a route. The not completely random arbitrariness of the idea seemed to be a pertinent mode of re-entry into the physical world. My signature would denote my location, not just my name. Geography would become an analog of thought.”

Seven tales later, the brief title story is a disorienting mix of horse-riding astronauts, cryptozoology, an obscure literary science experiment, vintage electronic musical instruments, and an enigmatic password. “She paused among the cabinets, feeling an affinity for these instruments that were never played and rarely looked at. They caused her to wonder about the meaning of collections. That meaning must lie in numbers greater than zero or one, because a collection of one thing seemed extremely unlikely. A collection of nothing could not be considered a collection. This led her to consider numbers less than zero. They would imply a negative collection, such as an art collector with no paintings. There might be a catalogue of all the pictures he did not own, some of them yet to be painted.”

The story called “Effects and Causes” intertwines European spies, a South American knotted-string form of writing, and basement rooms that only sometimes exist. “As far as he knew, quipus were used by South American peoples, the Incas among them, to record numbers. The coloured strands had meaning. The knots in them had meaning. The distance between the knots had meaning. It was all shrouded in mystery and had no meaning for him at all. And yet… What do you do if you desire meaning and there is none to be had? You make it.”

The protagonist’s search for meaning appears to conjure not only a room, but a book—a story within a story, in which a female spy reflects: “It was nerve-wracking working for both sides. Bad enough working for one. Two caused more than twice the trouble. Sometimes she took pride in her situation. She felt a heightened sense of reality and power. The civilians around her floated by like flat characters from a dream. But she also felt like an insect scurrying to avoid being crushed. Spy-craft was a side effect of humanity, it perverted the fundamental aspects of life. How could there be love if there was no trust?”

“An English Story” brings together in a pub four very British strangers with nothing in common but a sudden shared moment of bloodless violence and a peaceful, drunken death. It begins, “In a land of reclaimed rivers, pulverized minerals and wheeler-dealers, were three men who formed a psycho-anarchic syndicate. They all desired the same woman.”

A “psycho-anarchic syndicate”—ha!—the perfect economical phrase to describe a trio of misfits thrown together by pure chance with a barmaid: “Though she found each one of them unattractive, their individual qualities of humour, sensitivity and strength, when taken together, would make a tolerable human being.”

“Antifoni” is an atmospheric little yarn that in all earnestness proposes a Viking-like village of seafarers who build a concrete boat to take them on a search for better quality housing. “Stuva Grundlig stood on a bluff overlooking the sea… The sign in the dark sky above him was neither favourable nor malign, but it beckoned and he could not resist. Stuva was bearded and powerfully built, with a weakness that made him susceptible to exciting propositions. So this was it. Tomorrow they would leave.” Hmm, do these character names remind me of a certain Swedish furniture store?

Nineteen more short tales, varying in levels of seriousness and absurdity, in setting and subject, round out the volume. Seven Cries of Delight is a genre-buster. I’m not familiar enough with the historical tradition of surrealist writings to say where this book may fit. I suspect that fans of Magritte and Dali who have a literary bent will appreciate it. It carries a hint of Lewis Carroll but is more adult, a large dose of Borges but is more accessible. For a more contemporary comparison, perhaps the early work of Barry Yourgrau is apt. Or most recently, the highly lauded Ted Chiang. Chiang’s stories are more obviously science fiction, and in my view are not as free and funny as Newton’s.

But why compare? This is an unusual, entertaining, and thought-provoking collection. It contains genuinely metaphysical and visionary writing without clichéd New Age trappings. On its opening “Pseudepigrapha” page is a quote from Dali: “Ironing board, plucked chicken, seven cries, a peach. Eat this book.”

–Brent Robison, author of Ponckhockie Union, 2019

Excerpt: Luis Moreno ate his own shoes—both of them. It wasn’t as if he was adrift on an ocean, alone in an uncovered boat, driven half mad from drinking brine and from the radiation of the sun beating down relentlessly upon him, with no food but his shoes—in other words a desperate act for survival. It wasn’t that, although he might have felt it was.

Mr Moreno lived downtown. He was an office worker of scant importance to his employer, meaning that he could easily be replaced. This is exactly what happened the day he arrived at work in his socks. He offered no explanation. It was a silence almost as perverse as the contents of his strange meal. But nothing was known about that, and he quietly left just as he had arrived—shoeless. It was raining.

Moreno had determination, cutting strips of shoe leather and boiling them until they were chewable, grating the heels and eating them by the spoonful. The soles had been a challenge. It had taken six weeks.

“Nothing comes from nowhere” his father used to say. It was one of those many platitudes to which he was prone. To Luis as a boy they had always seemed to hold some undefined wisdom. From the vantage point of adulthood, he had come to think that these banalities were an unconscious attempt to grasp at meaning.

His father had spent his life working as a cobbler, as had his grandfather before him. Not so Luis. On account of his mother’s machinations with the church, he had been enrolled as a medical student in Madrid but he never became a doctor. He dropped out soon after starting. By the time he was twenty-five he was looking for a way to leave Spain. His short time as a student was spent associating with poets, painters and philosophers. It was a brief experience with lasting consequences.

Nothing came from nowhere, so everything must have come from somewhere. Over breakfast one morning in Madrid, he had set fire to his hair with a cigarette lighter. Already in his youth he displayed a penchant for impulsive acts but none of them were what they seemed. He had planned the hair burning for months, waiting for the quiff that swung across his forehead to grow long enough to be worth setting ablaze. Even the day had been carefully chosen, taking into consideration the people who would be present and their likely states of mind. It was a gathering of friends, all of them hungover from the previous night, including Luis. He suddenly roused them from their torpor by flicking his lighter and burning off his quiff—a part of his anatomy of which he was quite proud. It disappeared within seconds and never grew back the same way. His friends were all delightfully shocked. Luis had a wicked sense of humour. He was obviously one of those people—those surrealists.

Pingback: Seven Cries of Delight by Tom Newton wins 2019 Dactyl Foundation Literary Award | Dactyl Review