Sometimes a novel’s originality is less a matter of affirmation than an act of refusal. Refusal to go along with received ideas of how to tell a story or create verisimilitude or even how words signify. Saying no opens up new space, or at least points towards what has been neglected by complacence.

Craig Rodgers’ Drift (Death of Print, 156 pages) is such a novel. A dystopian tale of a bible salesman named Charlie, it will defy the ingrained expectations of many readers. Plotwise, Charlie has no trouble making a sale: everyone seems to want his product. He has no idea why. Women like Charlie—no struggles there, either. Other characters include a clown on a rampage and a mysterious goon in a dented bowler hat who seems to be following Charlie. There’s a bearded lady, with whom Charlie has sex, and a young boy afflicted by plague who becomes his travel companion. Then the boy steals Charlie’s car. Continue reading

Flash fiction has enjoyed a boom in recent years but sometimes overlooked are shorter prose forms which don’t respect the conventions of flash—e.g., at least an implied plot or hint of closure—in order seek out other literary effects. Thomas Walton’s All the Useless Things Are Mine: A Book of Seventeens (Sagging Meniscus, 138 pages) is an intriguing entry into this field. It is both experimental, in the sense that there isn’t really a label for the genre, and traditional, for it deploys aphorism and image in a manner which is readily accessible, despite its peculiarity.

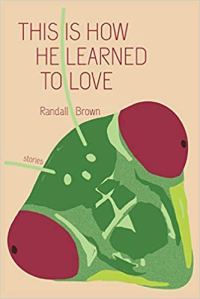

Flash fiction has enjoyed a boom in recent years but sometimes overlooked are shorter prose forms which don’t respect the conventions of flash—e.g., at least an implied plot or hint of closure—in order seek out other literary effects. Thomas Walton’s All the Useless Things Are Mine: A Book of Seventeens (Sagging Meniscus, 138 pages) is an intriguing entry into this field. It is both experimental, in the sense that there isn’t really a label for the genre, and traditional, for it deploys aphorism and image in a manner which is readily accessible, despite its peculiarity. Was it the intention of Randall Brown or his publisher to make a statement by putting the word “stories” on the cover of This Is How He Learned to Love (

Was it the intention of Randall Brown or his publisher to make a statement by putting the word “stories” on the cover of This Is How He Learned to Love ( When does a presence become a force to be reckoned with? A few years ago, I became aware of Stephanie Dickinson because her name often appeared in literary magazines. She was a prolific writer, popping up in many places. I’d read a few of her flash pieces, which were strong in imagery, but I’d never read an entire book of her work until now. Her latest collection of short stories, Flashlight Girls Run (

When does a presence become a force to be reckoned with? A few years ago, I became aware of Stephanie Dickinson because her name often appeared in literary magazines. She was a prolific writer, popping up in many places. I’d read a few of her flash pieces, which were strong in imagery, but I’d never read an entire book of her work until now. Her latest collection of short stories, Flashlight Girls Run (