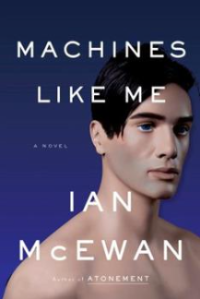

Machines Like Me (Nan A. Talese, 352 pages) by Ian McEwan is set in the possible world of the 1980s if Alan Turing had not died in 1954, Kennedy had not been shot in Dallas, and Britain had not won the war in the Falklands. In the story, Open Source information has allowed technological progress to sprint ahead, and the automatization of work is leading, first to high unemployment and then, presumably, to the creation of a universally idle population supported by the labor of machines. The hero, Charlie Friend, has recently purchased a life-like robot named Adam and he and his new love interest Miranda Blacke will together train and condition Adam to develop a personality and consciousness.

Machines Like Me (Nan A. Talese, 352 pages) by Ian McEwan is set in the possible world of the 1980s if Alan Turing had not died in 1954, Kennedy had not been shot in Dallas, and Britain had not won the war in the Falklands. In the story, Open Source information has allowed technological progress to sprint ahead, and the automatization of work is leading, first to high unemployment and then, presumably, to the creation of a universally idle population supported by the labor of machines. The hero, Charlie Friend, has recently purchased a life-like robot named Adam and he and his new love interest Miranda Blacke will together train and condition Adam to develop a personality and consciousness.

As per usual, this McEwan story is hung upon the frame of romance. The cloak this time is the nature of artificial intelligence. (I don’t mean to sound so cynical; McEwan is a talented writer; I’m just not intrigued by marriage plots.)

The question posed by Alan Turing in 1951, Can Digital Computers Think? is here interpreted to be a rhetorical one. For many years now and miles and miles of science fiction pulp, we’ve been conditioned to accept the inevitability that computers will be designed that will be intelligent in the way that humans are, only better, more logical, able to compute faster, with infallible memories and free from all the psychological misfirings to which humans are so prone.

The reason that we have to come expect this of our machines is because we have mostly adopted materialism. Unconsciously perhaps, we have answered the question posed by Turing with a non-sequitur: humans are machines.

But McEwan doesn’t write about this observation of mine. He sticks to the conventional script about AI. Important writers shouldn’t stick to conventional scripts. They should question them. So, there you have my judgement up front, which colored my reading of this otherwise marvelously told story. McEwan is a master at the realistic depiction of the interior lives of sensitive people as they confront existence. The novel begins,

It was religious yearning granted hope, it was the holy grail of science. Our ambitions ran high and low–for a creation myth made real, for a monstrous act of self-love. As soon as it was feasible, we had no choice but to follow our desires and hang the consequences. In loftiest terms, we aimed to escape our mortality, confront or even replace the Godhead with a perfect self. More practically, we intended to devise an improved, more modern version of ourselves and exult in the joy of invention, the thrill of mastery. In the autumn of the twentieth century, it came about at last, the first step towards the fulfillment of an ancient dream, the beginning of the long lesson we would teach ourselves that however complicated we were, however faulty and difficult to describe in even our simplest actions and modes of being, we could be imitated and bettered. And I was there as a young man, an early and eager adopter in that chilly dawn.

In this story examining the nature of consciousness, the rudder of our moral universe, McEwan supposes that AI will have moral superiority because computers will have access to more information and will be able to see right from wrong, insofar as they can only follow logic. There are some dozen androids like the Adam model (or the Eve model), and one of the developments of the plot hinges on the fact that when the androids witness moral depravity of humanity, they tend to commit suicide, which is the logical course, apparently, according to the author.

Charlie’s Adam is a bit different from the other amazing new androids, which have only recently rolled off the assembly line, because he has something “to live for”; he has fallen in love with Miranda and is inspired to write thousands of haikus. For some reason, this Adam is more inclined to try to right the wrongs of the world than to succumb to depression like his fellow androids.

As emotional and self-aware as Adam seems to be, he remains very unlike humans in important ways, as Charlie and Miranda soon enough discover. Adam begins to act on the sense of morality that he has garnered from his extensive experience with the records of human civilization. The reversal of fortune moment in this story comes when he gives away all their money and reports them to the authorities. Without knowing it perhaps, McEwan is rewriting the story of the Golem, in which the inhuman machine makes man follow the unforgiving letter of the law, ignoring what is important and sacred to human beings. In Machines like Me, the electronic hero, reports his beloved Miranda’s crime (of passion) to the police: she has framed a man for rape, who did not rape her, but did rape her friend, triggering her friend’s suicide. Miranda’s actions are strictly against the law and motivated by revenge, but they are understandable and forgivable in the eyes of Charlie—and most other people, including most readers, probably. McEwan imagines that Adam, as an android, is incapable of telling white lies or keeping things private, even if that means harming others that he loves. The law knows no mercy.

There is much speculation in the AI “space” these days (loathsome metaphor) about the possibility, nay the necessity, of wresting the reins of government out of the corrupt hands of disgusting humans and putting the people’s fate in the hands of an objective, disinterested AI. In the dystopian sci-fi telling of such tales, machines like Adam switch on and reenact the role of Golem, turning against their creators and showing no mercy, sticking to principle for the sake of principle, until they have eliminated the bi-pedal scourge of Earth.

The old Jewish myth of the Golem of Prague is about the dangers of bureaucracy and mindlessly applied law. A law is like a machine. A “programme” or an “algorithm” is a machine and Alan Turing used those terms in that way. We may say that a computer, as machine, is the in-substantiation of lawfulness and an artifact of a living system. And this is one reason why machines will never be alive. In truth, we make laws only as a scaffold against which flexible actions may be taken. Insofar as they are constraining, laws help make freedom possible. That’s how I would rewrite my Golem story. But, as I say, McEwan sticks to the traditional script.

Another popular, related theme that McEwan touches on in this story is the idea, that once we’re all equipped with neural implants and connected to the 10G Internet of Things and Bodies, there will be no secrets; no one will be able to commit a crime and conceal it; privacy will not exist; there will only be absolute transparency, and no one will mind or be embarrassed because everyone will be in the same boat.

Once upon a time, for a brief moment in my life, in my early idealistic teens, I wished that we could all read each others’ minds because expression is so difficult. My parents would finally be able to understand me; the boy I had a crush on would know how beautiful my mind was and fall in love with me instantly; people would stop fighting because they would understand each other perfectly.

I didn’t continue to wish that for very long and eventually came to cherish my privacy and my secrets, even the way I am misunderstood in the world, which is a little thrilling, in a way. The possibility that the entire history of our strokes on our keyboards and conversations recorded by always-attentive smart phones might be pulled up at any moment by a conscientious android is a horrific idea. No way around it. Total transparency is a state not to be wished for.

As the novel progresses, lots of theory about the nature of AI is ladled out in conversations between Charlie Friend and Alan Turing. It is no wonder why McEwan chose the conceit of this alternative history, for it is convenient to have the great mind of Turing explaining how computer designers were able to create the amazing androids. McEwan discloses that Turing did something with quantum something, somehow breaking determinism by somehow using some kind of quantum computing and DNA neural networks with quantum position something, and he thereby solved the P versus NP question. This led to automated discoveries of proofs. No longer were humans needed for that mathematical task. Machines could discover new laws, not just follow them. The rest is alternative history.

When some sci-fi story writers confront the problem of creativity, they often “solve” it by supposing it has something to do with randomness and they fill up the gaps of their understanding with the nebulous and opaque notion of quantum undecidability.

Turing did not necessarily answer his own question in the affirmative in that infamous 1951 essay—rather he explored the question of what thinking is, without finding an answer. He did predict in the “imitation game” paper that 50 years hence (it took more like 75), we would find it hard to tell the difference between chatbots and people because we can’t see inside the black box—which is true of our relationship with other humans as well.

In the final scene, McEwan’s Turing rebukes Charlie for killing Adam—who had become dangerous to Miranda and Mark, their soon-to-be-adopted son—because Adam “had a Self,” a quality which people tend to project onto future “smart” machines these days. I also noted that this alt-Turing dismisses the whole history of the study of the human mind because it produced “nothing predictive to give psychology a good name.”

I have doubts that the real Turing would have thought such things, at least not about the kinds of neural nets or LLM that we have today, which cannot be said to be capable of real creative work. We do not know that Alan Turing would have supposed that thoughts and actions of biological systems can be precisely predicted; his early work in the 1930s was appreciative of a creative person’s tendency to make mistakes and thereby discover new laws that a boring and accurate person could not. And his late work in morphogenesis had led him to the discover that random instability was the trigger to self-organizing biological processes, which were not, his research indicated, determined by genes. It is not the randomness that is the interesting part of this mechanism, but the order that emerges from it. When McEwan passes over this late work, he sees only it contributing to “computational biology,” which misses Turing’s larger point about indeterminism, which Ilya Prigogine, who had talked with Turing right before his death, ended up expressing in the 1970s.

But McEwan is a masterful story-teller and I enjoyed the book. There are some excellent descriptions that I will remember for ever, for instance, he relates a very enlightening description of what it might feel like to charge rather than to eat. Adam reveals that

In those first seconds, it was a gorgeous surge, a breaking wave of clarity, that settled into deep contentment.… The first touch [of direct current is] like light pouring through your body. Then it smooths out into something profound. Electrons, Charlie, the fruits of the universe, the golden apples of the sun…. You can keep your corn-fed roast chicken.

Early on, McEwan refers to “an absurd leap of understanding into what one already knows” and I coupled that with an observation made late in the novel about the body knowing things before the mind grasps them. I believe this shows McEwan has a very deep sense of human intuition, which AI designers always seem to lack.

There are things that a great writer does that can be formulated and copied. When I’m reading a writer I admire, I take note. I liked, for instance, the way McEwan introduces an important character, about whom much has been said, but who has not yet come onto the stage. When he describes Miranda’s father for the first time, he first circles around the man’s context with a keen eye, and ends bull’s eye on the man. It has a mock heroic effect:

The room was as large as any in Elgin Crescent [the home the couple is keen on purchasing], floor to ceiling bookshelves on three sides, three sets of library steps, three tall sash windows overlooking the street, a leather-topped desk, dead center with two reading lamps, and behind the desk, an orthopedic chair packed with pillows and among them, sitting upright, fountain pen in hand and glaring across at us in focused irritation as we were ushered in, was Maxfield Blacke…

Then the old man shouts, “I’m right in the middle of a paragraph, a good one,” and tells his visitors to come back later.

This is excellent Dickensian characterization. Bravo, Mr. McEwan. But I’ve analyzed this passage and I believe I can formalize it in such way that I can imitate it in my next book. My version won’t be thought of as plagiarism because it will only be the form of the passage not the words themselves that I will copy.

Maybe AI will be conscious some day, maybe it won’t. The fashionable thought these days is to suppose that it will be. I disagree, not because I believe in spirit or an élan vital but because I understand how the poetic power of immaterial relationships can create unpredictable effects. I don’t expect a great writer to rehearse the stereotypical story for our age with artful language and nice devices. Soon a better ChatGPT, employing formulas for good Dickensian writing such as I have noted, will be able to do that. I expect a great writer to relate a perspective for which there is no formula yet.

–V. N. Alexander, author of Chance the Mimic Choice (still unpublished)