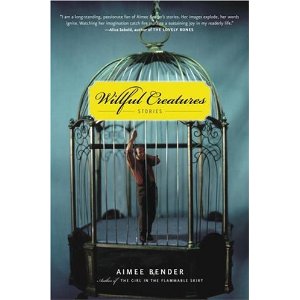

Aimee Bender’s stories are the contemporary descendants of those of the Brothers Grimm, with their surrealism laid on top of human desire and need. In both her previous collection, The Girl in the Flammable Skirt, and this newest one, Willful Creatures (Doubleday, 224 pages), her fiction adopts the tone of fairytales through the straightforward storytelling of the bizarre. Instead of a sausage growing on the end of a nose, Bender gives us potato children and a captive miniature man. Instead of a wicked stepmother, she conjures a collective group of predatory teenage girls. The “willful creatures” of the title take over and change the lives of the people who discover them. While some of these creatures have irons for heads or are made of glass or have keys for fingers, many appear, at least superficially, as ordinary people living routine lives.

Aimee Bender’s stories are the contemporary descendants of those of the Brothers Grimm, with their surrealism laid on top of human desire and need. In both her previous collection, The Girl in the Flammable Skirt, and this newest one, Willful Creatures (Doubleday, 224 pages), her fiction adopts the tone of fairytales through the straightforward storytelling of the bizarre. Instead of a sausage growing on the end of a nose, Bender gives us potato children and a captive miniature man. Instead of a wicked stepmother, she conjures a collective group of predatory teenage girls. The “willful creatures” of the title take over and change the lives of the people who discover them. While some of these creatures have irons for heads or are made of glass or have keys for fingers, many appear, at least superficially, as ordinary people living routine lives.

One of the most memorable stories is “End of the Line,” where a big man buys a little man from a pet shop, keeps him in a cage with a television and sofa, and commits unspeakable cruelties. “The Meeting” starts out like a Talking Heads song of the late 1970s: “The woman he met. He met a woman. This woman was the woman he met.” From this staccato, inane beginning, the story develops the theme of ruined expectations and how they can evolve, without warning, into powerful emotions. “Dearth” is the story of a childless woman who discovers a pot of persistent, magical potatoes that grow into children. In “The Case of the Salt and Pepper Shakers,” the narrator, a crime investigator, is less concerned with how a husband and wife killed each other at the same moment than he is with the mysterious collection of fourteen salt and pepper shakers he finds in their house.

Readers won’t confuse Bender’s work with anyone else’s. Her inventive plots, coupled with no-nonsense language, result in swiftly told tales. To Bender, contemporary life is as mysterious as words made of xenon, and yet she manages to give us glimpses of raw emotional truth. Staunch realists and literalists might find themselves left cold by Bender’s unconventional fiction, but those willing to accept a stark, matter-of-fact surrealism will be enchanted.

—Debbie Lee Wesselmann, author of Trutor and the Balloonist (1997) and Captivity (2008).

excerpt

Death Watch

Ten men go to ten doctors. All the doctors tell all the men that they only have two weeks left to live. Five men cry. Three men rage. One man smiles. The last man is silent, meditative. Okay, he says. He has no reaction. The raging men, upon meeting in the lobby, don’t know what to do with the man of no reaction. They fall upon him and kill him with their bare hands. The doctor comes out of his office and apologizes, to the dead man.

Dang it, he says sheepishly, to his colleagues. Looks like I got the date wrong again.

One can’t account for murder or accidents, says another doctor in his bright white coat.

The raging, sad men and the smiling man all leave the office. The smiling man does not know why he is smiling. He just feels relieved. He was suicidal anyway. Now it’s out of his hands. The others growl at him, their bare hands blood specked, but the smiler is eerie in his relief, and so they let him be, thinking he might somehow speed up their precious two weeks. The raging men tear out the door first; the crying men follow.

On their way they meet up with a field of cows. The cows are chewing quietly and calmly. The sight of the cows fills the crying men with sadness as they only have two weeks left to look at cows. But the sight of the cows fills the raging men with more rage. After all, why are the cows so calm? Why is it that cows get to remain ignorant of their own death? Why is the sky so blue and peaceful? The raging men run to the cows but the cows don’t notice; the cows want, more than anything, just to continue chewing. One raging man collapses in the field and drums it with his fists. The others run and run. The five crying men stand at the fence, crying. Look at the sad and large rage of the doomed men, they think. Who knew a cow was so beautiful? Why was I not a farmer? Why not a field hand? Why an office building?

Back at the office building, the doctors check their notebooks and discover an error. Oops. Only two of the five crying men need to be crying. The other three are in perfect health. The doctors, embarrassed, call up their patients who are by then crying into the arms of their crying wives or lovers or pets.

We have some good news! they say. We made a goof. You seem to be in perfect health. Very sorry about that.

One crying man, new lease on life, moves his family to the countryside where they raise goats.

The other two go back to their regular routines. A close call.

The last raging man still is drumming his fists on the field. His lover calls out into the darkness of the night. The lover understands that his angry man is out there raging against the world again, this is to be expected, but he does not understand why the doctor keeps calling.

The suicidal one is another error, but he is impossible to contact. He has flown by now to Greece and is trying finally to have a relationship. With only a couple of weeks left, he thinks that for once he has a good chance of having someone by his bedside when he dies.

The two remaining crying men die. One with tubes, the other in his own bed. One of the raging men dies, roaring in his bathtub. Another, though not a mistake, still drums that field with his fists. The very energy it takes should drain him dry, but no. He is happily drumming. He drums for weeks and sits up and isn’t yet dead. It takes him six months, which he uses to make some angry paintings that are beloved by people in galleries who are unaware that they themselves are angry at all.

The Greek woman sobs when she hears that her wonderful melancholy lover will be dying soon. They do ritual after ritual. Their sex is like castles; it has moats and turrets. If only, thinks the suicidal man, if only I had known for longer how short it all would be.

Everybody says this. They say it for us, the nondying, to remember our daily lives. But we can’t fully get it until we’re right up in the face of it. Can we get it? It is hard to get. I do not get it. Only the suicidal man gets it here, and his Greek lover with her aquiline nose….

Pingback: Δήμητρα Ἰ. Χριστοδούλου: μικρομυθοπλασία: στὰ ἄδυτα τῆς σύγχρονης ζωῆς | Πλανόδιον - Ιστορίες Μπονζάι