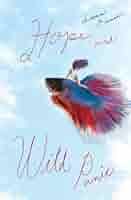

Some writers refuse to get in line with linearity, or take up common cause with causality. In Sean Ennis’s Hope and Wild Panic (Malarkey Books, 202 pages), the reader finds a depiction of life in the contemporary U.S. with recognizable settings and characters—realism, in a word—but it is also fundamentally destabilized, relying on non-chronological fragments (chapters? flash fictions?) of only one or two pages to explore the lives of a middle-aged narrator and his family. One section begins as follows:

“Rejoice with me, I have beaten psoriasis. There’s this trick I have of not watching the news. Most things don’t happen, and there’s been some debate internally about the order of events. I keep losing things and the obvious answer is that they’ve been stolen! But the investigation is finished—it is what it is. A black government helicopter is circling, and I’m just reading my big heavy book like that’s just a ceiling fan. Our neighbors behind the house, across the gulch, have been growing marijuana. I wonder what for. A family of foxes is our other neighbor. Is there some apophenia going on here? Doot-dee-doo.”

If, like me, you need to look up “apophenia” (“the tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things”—thank you Merriam-Webster!), it’s worth the effort, because it not only clarifies the preceding sentences, it also offers a glimpse into a sensibility. Hope and Wild Panic is not the sort of “big heavy book” that pretends to explain everything by putting up a mirror to the world. But, short of understanding what is going on, and what it means, Hope and Wild Panic does an estimable job of capturing how, at this moment in our culture, life feels.

An earnest faith in verisimilitude and transparent language as the path to truth now seems, artistically speaking, naïve and unrealistic: a chimera of the 19th and 20th centuries. At the beginning of this century, James Wood used the phrase “hysterical realism” in regard to writers like Zadie Smith and David Foster Wallace, who faithfully transcribed everyday detail while employing manic or highly-wrought prose: the amped-up style was seen as the latest way of trying to salvage the project of rendering the “real” world.

Ennis, too, leans heavily into style—but, for this writer, the manner isn’t hysterical. Tonally, the narrative voice is often laid-back, unassuming, and the prose is definitely not maximalist. Rather, his stylistic signature operates at a more fundamental, syntactic level, favoring links by association instead of conventional signposts and transitions. Cause and effect cannot be taken for granted.

“I am mainly private, wear socks to bed for emergencies. This accounts somewhat for the lack of followers to my personal faith and for never riding around a room on a chair. I think it’s wrong to brag and everything is a brag. It’s hard to tell stories.”

Hard indeed! Perhaps now we live in an era of apophenic realism. Ennis’s narrator lives in a college town in Mississippi, with his wife Grace, a professor, and a growing son. He works as a tutor for large young men on athletic scholarships. In other hands, this would be a ready set-up for a bit of Tom Wolfe-ish satire, as in I Am Charlotte Simmons. But Ennis, though often humorous, avoids easy or predictable jokes. His narrator actually loves his wife and likes his students. Campus politics don’t particularly interest him, either. He muses, “I’ve been accused of having no ideology, but I’ve got plenty! And sometimes I just go with the algorithm.”

The fragmentary sections of Hope and Wild Panic can be read as flash fictions or as constitutive of a novel. I incline toward the latter, because although there is not much of a plot (unless you consider that there are 80 plots), there is unity of place, of characters, of tone. Moreover, the lack of a conventional story arc can feel more true-to-life than the contrivance of a tidy plot. And, apophenia aside, Ennis is not averse to closure: for instance, in the very satisfying sequence of seventeen sections bearing the same title as the book, “Hope and Wild Panic;” or even within the confines of a single paragraph, which tells a complete story:

“We were all at this poetry reading—the poet was from out of town and competing for a job. Every other person in the room knew the hiring would be internal, and he had no shot. This insight seemed to dawn on the man during his third poem, which was an extended metaphor about the dangers of microplastics. He suddenly looked embarrassed and terrified. It was heartbreaking, but, yes, kind of poetic.”

The book is full of such encapsulations, at turns unsettling and funny. Sometimes collections of flash fiction, even good flash fiction, can be hard to appreciate as a whole, because the effect is like looking into a strobe light. But Ennis defuses that problem with a consistent and beguiling voice. As a novel, or novel-in-stories, or linked stories—whatever one chooses to call it—Hope and Wild Panic renders a world at once recognizable and strange, and yes, bracingly real.

___________________________________________________________

Charles Holdefer’s recent books are Don’t Look at Me (novel) and Ivan the Terrible Goes on a Family Picnic (stories).