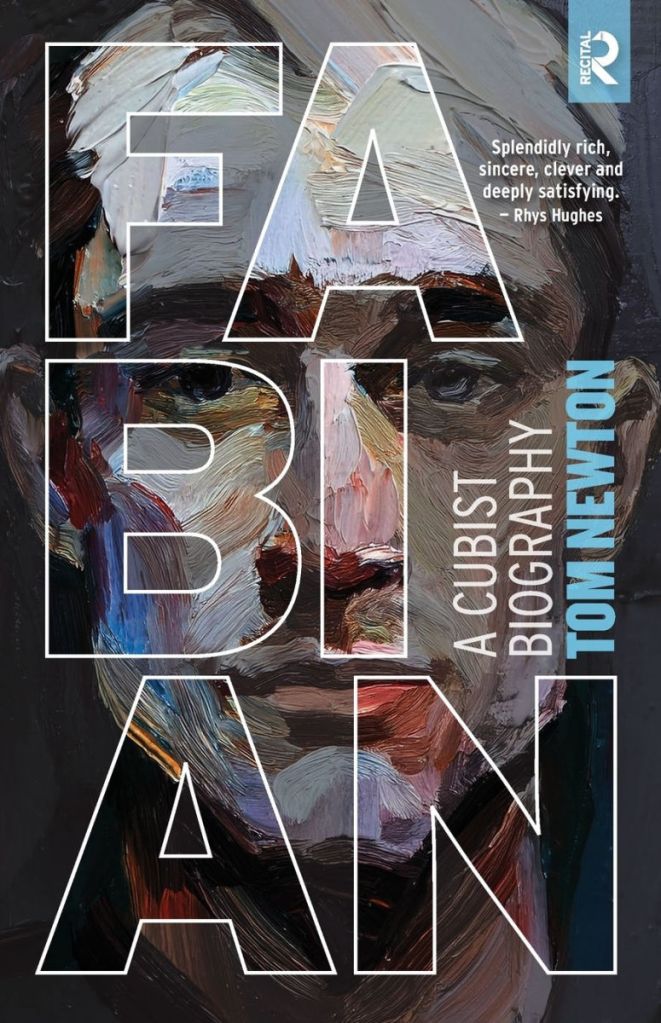

Tom Newton’s latest novel, Fabian: A Cubist Biography (264 pages Recital Publishing), presents itself as a biography of Fabian, a “disillusioned, would-be filmmaker.” Fabian, a civil servant in the British Ministry of Information during WWII, longs to make a groundbreaking film, but never quite does it. He creates a treatment. He thinks through his artistic desire. Leaving off a Godot-like deferral of Fabian’s planned film, the novel careens fantastically through epochs and ideas. We encounter Spanish conquistadors and Aztec priests, Dr. French (a time-traveling psychoanalyst), Junita (another enigmatic time-traveler) and more. Everyone has a backstory and place in intertwined narratives, arriving at a resolution that challenges the notion that a good book should tuck every loose end in place.

Fabian is an amazing and compelling composition. Two aspects of the novel make it particularly engaging. The first and most forward-facing is the meta-focus of its construction. We are quickly clued in that we are not about to read a standard biography. The book opens with a preface by “Tom Newton,” a persona with the same name as the author on the cover but who dates his entry “1837,” a nonsensical assertion if this persona corresponds to the name assigned the copyright in the front matter. We then are shunted into the primary tale of Fabian the filmmaker which tracks him through a relatively conventional portrayal of the hero’s early life. Fabian wants to make films, and he does get a foothold in a film career working for the WWII British Ministry of Information; but his great project dissipates. The novel then departs from Fabian to the story of a young man, also named Fabian, swept up in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire. Layers of characters and time are added. We encounter Dr. French, a flimflam psychoanalyst who, Dr. Who-like, appears in different eras according to a logic that is never explained. We also meet Juanita, an avatar who emerges in three different epochs, each with a unique, spellbinding narrative. All the while, Tom Newton tosses in questions and assertions that cast doubt on the conventions of novels that have driven the art form for centuries. What is truth and what is fiction? Who sets the rules of the game? Why should the reader play along? Fans of Paul Auster’s fiction will be familiar with the sly goal post-resetting that makes a meta-form a fun puzzle.

The second and more viscerally compelling aspect of Fabian are the individual stories of the primary characters. The novel gains a palpably different energy by changing epochs, introducing Fabiàn, a young man about to sign up for the conquering army of Cortes:

“By the fingernails of Christ!”

That’s when things took a turn for the worse. The man opposite him stood up from the table, knocking over the bench behind him. He was a big man and his ugly face was wracked with a spasm of fury. He spluttered his oath and Fabiàn felt the spittle on his cheeks and lips.

Newton can spin a yarn; he is a genuine story-teller who embraces time-honored emotional logic of story-telling within these sub-stories. Newton goes pages without a hitch in the narrative to remind us we are reading a narrative. Until a narrative hitch comes up and the game changes.

What to make of these competing truth claims? An essential thing to understand about Fabian is buried in plain sight; it is the word “Cubist” in the subtitle. Cubism was an aesthetic movement arising in painting and visual the arts in the early twentieth century. It sought to render not a portrait of the world but a sense of it in ways more suggestive and inferential than the representational art of preceding decades. This new aesthetic made little attempt to replicate human and other organic figures realistically. Figures were broken down into fundamental forms that were then reassembled into a surprising visual construction that conveyed truths about apart from literal mimicry. Cubism sought to induce or evoke a truth rather than replicate it.

I find literary definitions of Cubism are not very effective without a visual support. One of the most notable Cubist paintings is Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, by Marcel Duchamp, pictured below.

Duchamp visually elicits a woman stepping down a staircase by fragmenting a female form into multiple sub-forms and linking the fragments through an implied temporal sequence. The abstract, blockish elements suggest a female figure traveling downward. It takes imagination and empathy of the viewer to grasp the vision, but the woman is there, maybe not precisely, but certainly in some way. Cubism is a deferred holistic experience; deferral until culmination arrives. Deferral is, so to speak, a binding element.

The literary dynamic of Fabian is something like the visual dynamic of Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2. Partly, Fabian’s uncanniness comes from mingling characters and eras, with traits that overlap; it also descends from the Newton’s deep familiarity with eliciting weirdness through arcana.

This leads us to Newton’s fascination with astrology and other hermetic arts, shown not only in the story of Fabian but in the appendices that end the book. As the poet Kenneth Rexroth wrote in his essay The Cubist Poetry of Pierre Reverdy, “What is Cubism in poetry? It is the conscious, deliberate dissociation and recombination of elements into a new artistic entity made self-sufficient by its rigorous architecture.” Although Rexroth focuses his essay on pioneering poetry, his insights have corollaries in narrative prose. Thus, “Poetry [and prose] such as this attempts not just a new syntax of words. Its revolution is aimed at the syntax of the mind. Its restructuring of experience is purposive, not dreamlike, and hence it possesses an uncanniness fundamentally different in kind from the most haunted utterances of the Surrealist or Symbolist unconscious.”

But we can push this insight still further. The deeper appeal of Fabian rests on an unspoken metaphysical impulse. Returning to Rexroth on Cubist poetry,

When the ordinary materials of poetry are broken up, recombined in structures radically different from those we assume to be the result of causal, or of what we have come to accept as logical sequence, and then an abnormally focused attention is invited to their apprehension, they are given an intense significance, closed within the structure of the work of art, and are not negotiable in ordinary contexts of occasion. So isolated and illuminated, they seem to assume an unanalyzable transcendental claim.

Fascination with the mystical underwrites Fabian; it is the signifier of a transcendental claim. Newton never tires of reflecting on eternal conundrums of existence: paradoxes, temporal flow, rendering truth, among others. This is the mysticism of the epiphenomenal. But rest assured, a congenial mood drives the narrative craft. None of this is nihilistic or petty. Much of the piece succeeds by charm—the charm of good writing and the charm of the sensibility crafting the work. Let us call him Tom Newton. This Tom Newton, who owns the copyright to Fabian, is treading the same path as Don Quixote and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. Like both classics, Fabian is mind-bending, and a devil of a good read. Perhaps, in the end, Fabian is less about authenticity versus illusion or the limits of narrative than about something more enduring. Fabian reminds us that the revolution is always happening, and that complacency is the foe.

–Vic Peterson, author of The Berserkers

Pingback: Winding Up the Week #456 – Book Jotter