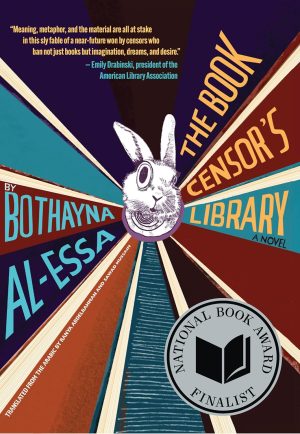

Translated by Ranya Abdelrahaman and Sawad Hussain

Book reviewers of “dystopian” novels often focus on how well iconic authors “predicted” our current world of mass surveillance, alternate realities, and grinding political crises. This helps determine whether they are classics. Orwell foresaw a forever-war of three great powers. Huxley anticipated mass-drugging of the populace. Margaret Attwood’s fear of male power hegemony crushing women’s autonomy and human rights still feels acute.

Then comes the inevitable, punctilious criticism of the iconic author for having forecast incorrectly. Orwell’s totalitarian state has been overtaken by a less comprehensive but more efficient model of regional autocrats. Huxley missed the rise of computers and the digital revolution. Attwood’s dark vision is limited by the unconscious biases of the feminism of the 1980s.

Such tea-leaf reading makes Bothayna Al-Essa’s The Book Censor’s Library (Restless Books, 261 pages) refreshing; it is couched as a fable, blessedly free of futurism. Yet it is biting, partly because of its uncanny charm, and partly because it is aimed at one contemporary autocratic regime, the Emirate of Kuwait. Al-Essa leaves little wiggle-room that the target of her satire is a living example of authoritarian power—and an example that becomes a stand-in for any authoritarian state.

Bothanya Al-Essa is a notable Kuwaiti novelist who has become prominent in modern Arabic literature. Much of her reputation arises from the novel that is the subject of this book review, The Book Censor’s Library, first published in Kuwait in 2019 and appearing in English translation in 2024. The story, set in an unnamed imaginary country, follows a government book censor whose job is to identify and suppress prohibited literature. As he meticulously checks books for subversive content, he becomes consumed by the literature he is tasked with controlling. Soon, he is enthralled by Zorba the Greek, Alice in Wonderland, Kafka, Dostoeyezky, and other classics—timeless stories that challenge imagination.

Like others in the dystopian clan, the Book Censor’s Library give a list of rules for censors what to banish that acts as a compass for the reader: Every word has only one meaning, which is approved by the censorship authority; a book censor may not spend time on a book past the time allotted by the authority; and,

“A book censor must ban all books that address forbidden subjects such as philosophy, semiotics, linguistics, hermeneutics, sociology, politics, and other such useless topics.“

There are ten rules in all. The literary baseline for the regime is literalistic, utilitarian, and bland. Only approved religious texts can be circulated. There is no latitude for interpretation.

Still, through the cracks in the censorship procedure, certain books become unexpected touchstones for the protagonist. He falls in love with several literary classics, which break the boundaries of thinking so rigidly policed in his everyday life. As the censor falls deeper under the spell of literature, he comes upon an underground resistance movement working to save banned books. The censor is recruited into the group.

Suppressing the imagination is key. Another set of maxims is given to the censors:

“Human existence is suffering.

The root of suffering is desire.

The root of desire is imagination.“

The book censor appears to suffer a fate similar to Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four: final assimilation by the all-controlling regime. Yet a figure from his past emerges in a daydream, a mentor who had shown the book censor how to secret away books from the infernal machine of suppression. In an uplifting speech, wonderfully without irony, the old mentor declares:

“You can’t ban imagination, no matter what you do.” The old man’s voice rang out inside of him [the book censor]. “You’ll never be able to stop it. It’ll swell up and start pumping its offspring into the world, one after another: Geppetto, Alice, Big Brother, Zorba … Bastards of the imagination, one and all, born of the forbidden world, even if they forget—or pretend to forget—where they came from.”

The life of the mind equals freedom. Apropos of this mood, the novel incorporates surreal and meta-fictional elements, blurring the boundaries of reality. But, of course, the poignancy of Al-Essa’s achievement is that she created a book that passed the censors of her own country. The escape hatch of the imagination can work. Her book is a fable that lifts us out of the present in ways sci-fi cannot. We are not tied to a “manifest destiny” or technology driven view of the future; rather, we are forced to confront the terrors of the present, and our ability to choose.

The culmination of the book is delicious because it mirrors the virtues it espouses: I cannot say more without spoiling the fun. It does not indulge in prognostication; rather, it has universal appeal because it identifies imagination as a fundamental element in humanity. Translators Ranya Abdelrahaman and Sawad Hussain have done a wonderful job conveying a blithe yet deadly serious tone. Dystopian stories are critical in explaining why every generation feels we are about to be crushed by overwhelming moral darkness: the feeling has always been with us. It always will be. It is how we protect existence.

Reviewers using the term “prediction” miss the mark, engaging in another kind of literalism. Beware of those lamenting an author’s technological missteps, losing sight of a novel’s real impact, an assessment of the present. As if to underscore Al-Essa’s fears, in 2024, the Emirate of Kuwait dissolved parliament and suspended key articles of the constitution, ostensibly for a limited time. Dostoyevsky wrote, “Beauty will save the world.” Let us hope.

-Vic Peterson, author of The Berserkers, 2022