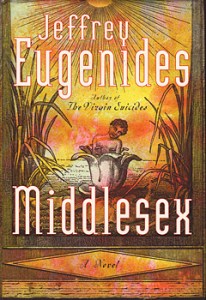

Like a hermaphrodite, Middlesex (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Jeffrey Eugenides is composed of two parts that are not usually joined together.

Like a hermaphrodite, Middlesex (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Jeffrey Eugenides is composed of two parts that are not usually joined together.

The first half of this 529-page novel is a memoir of an average Greek-American family living in Detroit. I was expecting a story about a person with genetic mutation that deeply affects his identity and sex life, but what is presented in that first half of the novel is a nostalgic tale of a Greek couple fleeing the Greek-Turkish war in 1922, settling down, in what was then becoming the Motor City, having children, running into financial problems, and surviving a race riot.

None of this had much to do the immigrant couple’s grandson (née granddaughter, apparently). That novel didn’t start until the chapter called “Middlesex” on page 253 where an amazing coming-of-age story finally begins to unfold. Cal/Calliope was born with undeveloped genitals and was mistaken for a girl until puberty started to try to catch his body up at fourteen. Continue reading

Although far from Bukowski’s best,

Although far from Bukowski’s best,