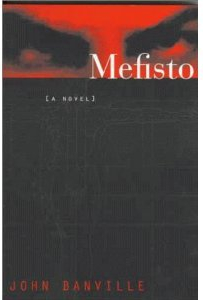

Gabriel Swan is the Faustian hero of Mefisto (Godine Press, pages 233). He is a savant mathematician, with talents that will make him out-of-place among uneducated poor Irish. With a desire to understand the truth of the universe, he believes that numbers will help him sense some “larger” pattern tying everything together. But as in Faust, what Swan does with his opportunities is disappointing. He hooks up with scam artists and junkies and, tragically, ends up being instrumental in his mentor’s efforts to prove there are no larger patterns. Continue reading

Gabriel Swan is the Faustian hero of Mefisto (Godine Press, pages 233). He is a savant mathematician, with talents that will make him out-of-place among uneducated poor Irish. With a desire to understand the truth of the universe, he believes that numbers will help him sense some “larger” pattern tying everything together. But as in Faust, what Swan does with his opportunities is disappointing. He hooks up with scam artists and junkies and, tragically, ends up being instrumental in his mentor’s efforts to prove there are no larger patterns. Continue reading

Tag Archives: philosophical themes in fiction

Ravelstein by Saul Bellow

Ravelstein (Penguin 233 pages) is based on intellectual and historian of ideas Allan Bloom, whose Closing of the American Mind stands as the meat to this ultimately gossipy, but not unrevealing, portrait of the man (closet gay, incorrigibly sloppy, resolutely positive, a big cigarette-smoking pizza-eating exquisite furniture-buying Saint Bernard of a man who plays Platonic soulmate matchmaker for his students, and gives his Chinese helpmate a car when he finally makes it big). Bellow apparently urged Bloom to write the book (which despite its reputation as a narrow conservative tract is actually a brilliant example of applied Platonism) which became a huge best seller, and for which the novelist wrote the introduction. Continue reading

Ravelstein (Penguin 233 pages) is based on intellectual and historian of ideas Allan Bloom, whose Closing of the American Mind stands as the meat to this ultimately gossipy, but not unrevealing, portrait of the man (closet gay, incorrigibly sloppy, resolutely positive, a big cigarette-smoking pizza-eating exquisite furniture-buying Saint Bernard of a man who plays Platonic soulmate matchmaker for his students, and gives his Chinese helpmate a car when he finally makes it big). Bellow apparently urged Bloom to write the book (which despite its reputation as a narrow conservative tract is actually a brilliant example of applied Platonism) which became a huge best seller, and for which the novelist wrote the introduction. Continue reading

Black Dogs by Ian McEwan

Rarely does it seem that a great writer is recognized in his time, but Ian McEwan is an exception. Using the trope of two black mastiffs left behind by the Gestapo but still menacing the beautiful French countryside, in Black Dogs (Nan A. Talese, 149 pages) McEwan tells the tale of an older couple June and Bernard Tremaine, living in different countries but still in love. The clever narrator, their son-in-law whose own parents died when he was eight, pieces together the interlacing of the private lives and world events of his adoptive parents from deathbed interviews with once-stunningly beautiful June and her big-chinned rational Marxist politician husband. The action toggles in space and Continue reading

Rarely does it seem that a great writer is recognized in his time, but Ian McEwan is an exception. Using the trope of two black mastiffs left behind by the Gestapo but still menacing the beautiful French countryside, in Black Dogs (Nan A. Talese, 149 pages) McEwan tells the tale of an older couple June and Bernard Tremaine, living in different countries but still in love. The clever narrator, their son-in-law whose own parents died when he was eight, pieces together the interlacing of the private lives and world events of his adoptive parents from deathbed interviews with once-stunningly beautiful June and her big-chinned rational Marxist politician husband. The action toggles in space and Continue reading

The Proud Beggars by Albert Cossery. Translated by Thomas W. Cushing.

I often wonder about sentences – about their impact, their purity, their necessity of being. I wonder about wasted words, wasted pages, and wasted stories. I wonder every time I read.

I often wonder about sentences – about their impact, their purity, their necessity of being. I wonder about wasted words, wasted pages, and wasted stories. I wonder every time I read.

Yet, whenever I reach for The Proud Beggars (Black Sparrow Press, 190 pages), I find myself in awe, mesmerized, a captive to Cossery’s mastery of language, his scenes, his characters, and his ideology. If there ever was the perfect literary book, for me, it is this one. Continue reading

The Names by Don DeLillo

DeLillo surely kept a journal while living in Athens and visiting various places in the Middle East and India. He noted scenes, described the climate and vegetation, philosophized on the locals then published his journal as the novel, The Names

DeLillo surely kept a journal while living in Athens and visiting various places in the Middle East and India. He noted scenes, described the climate and vegetation, philosophized on the locals then published his journal as the novel, The Names (Vintage, 352 pages), after he added a “plot” about a cult that murderers people for the completely uninteresting reason that their initials match the initials of the place name in which they are murdered. DeLillo also added the equally uninteresting denouement in which it is

discovered that the narrator, who has been described as a Continue reading

discovered that the narrator, who has been described as a Continue reading

Black Dogs, by Ian McEwan

Black Dogs: A Novel

Black Dogs: A Novel (Nan A. Talese, 149 pages) is a skillfully written novel on an interesting and profound topic. McEwan does a wonderful job describing June, an eccentric old woman, the narrator’s mother-in-law. He also handles what could be a very artificial story device in a reasonably natural way. The idea of the book is to explore the conflicts between mystical thinking and rationality, and the narrator is interviewing and writing a memoir on his mother-in-law and father-in-law who represent those views respectively. This passage exemplifies well McEwan’s sensitivity and talent as a writer; Continue reading

The House of Meetings by Martin Amis

The House of Meetings (Knopf, 256 pages) is a narrative delivered as a long letter from an unnamed narrator, an 86-year-old Russian man, to his step-daughter Venus, living in Chicago. He is in the midst of traveling back home after many years in the U.S. The point of his journey is to revisit a work camp in the Artic where he had been held prisoner and slave laborer in the 40s and 50s. Particularly, he wants to visit the “house of meetings,” where, late in the labor camp era, the Soviets had begun allowing some prisoners to meet briefly with their wives. The narrator’s brother, Lev, Continue reading

Continue reading

Walk On, Bright Boy by Charles Davis

Set in Medieval Spain, Walk On, Bright Boy (The Permanent Press, 144 pages), a story of a boy’s first confrontation with political and religious corruption, strives less for historical accuracy than for universal applicability. Written with lovely economy and sensitivity, it is reminiscent of a fable or of a young adult coming-of-age tale. At the same time, however, it is also complex in its exploration of human foibles and conflicting philosophies.

Set in Medieval Spain, Walk On, Bright Boy (The Permanent Press, 144 pages), a story of a boy’s first confrontation with political and religious corruption, strives less for historical accuracy than for universal applicability. Written with lovely economy and sensitivity, it is reminiscent of a fable or of a young adult coming-of-age tale. At the same time, however, it is also complex in its exploration of human foibles and conflicting philosophies.

Continue reading